Why Maslow’s Pyramid Often Works in Reverse for the Gifted

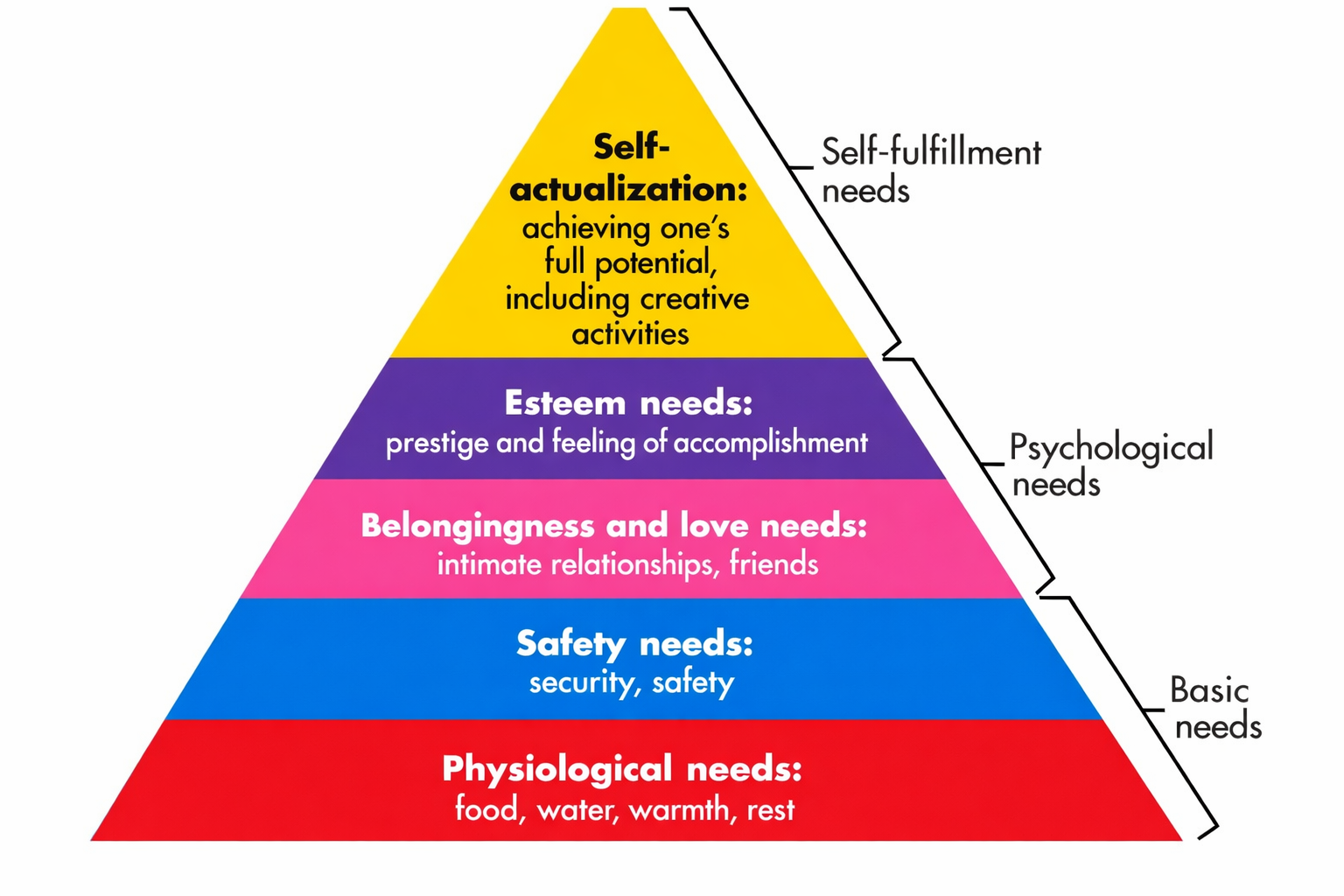

Psychologist Abraham Maslow famously described human motivation as a hiërarchy of needs, later to be simplified into a pyramid by others: first we take care of our physical needs, then safety, belonging, and status and only then do we focus on meaning, purpose, and self-actualization. For many gifted people, especially the highly and exceptionally gifted, this order does not match their lived reality. They often start at the top and seem to live by a reversed piramid.

Rather than being primarily motivated by safety, comfort, social belonging, or material security, many gifted individuals are driven first and foremost by meaning, truth, beauty, coherence, and the “why question.” Their inner compass points upward, not downward.

For the gifted, the pursuit of the intellectual or creative quest is often more important than safety, comfort, or even self-preservation. Questions like “Why does this matter?”, “What is the underlying truth?”, or “What is the most elegant solution?” can be more motivating than money, comfort, social alignment or even security. As a result, practical needs such as routine, financial stability, or basic self-care are sometimes postponed or quietly neglected.

Or in Gifted Hunter terms: The Hunt matters more than the Campfire. This is not a character flaw. It reflects a different motivational architecture, one that becomes visible when we look closely at how gifted people actually live and work.

Sounds Familiar?

We’ve all been there. Forgetting to eat, when caught up in work that’s important to us. Forgetting an appointment, when just having found some new website or fascinating topic that grabs our full attention. Pretty harmless, yes? When this happens incidentally it is. But for many gifted people this takes on a habitual pattern that does cause them harm. Physical, relational and often financial: “Pension plan? What pension plan?”

Often they skip several steps in one go so the it seems like they are really living with a reversed hiërachy of needs.

Three common Maslovian side-steps seen in the lives of the gifted are:

1. A gifted researcher becomes fully absorbed in a complex problem or creative breakthrough. Days blur together. Appointments forgotten. Meals are skipped, sleep is shortened or fragmented, bodily signals are ignored.

What steps are bypassed

Physiological needs: sleep, regular eating, physical recovery

Belongingness and love needs: approval, group inclusion, relational safety

What step is prioritized instead

Self-actualization: mastery, creation, truth, elegance, insight

Risk if sustained

Burnout, immune suppression, isolation, chronic exhaustion, or a sudden physical crash that feels “unfair” to the mind.

2. A Gifted Hunter leaves a stable, well-paying job because the work feels meaningless, unethical, boring, claustrophobic or intellectually dead. They move into uncertainty: freelance work, a startup, a creative or intellectual path with no guarantees.

What step is bypassed

Safety needs: financial security, predictable income, stability, career protection

Esteem needs: prestige

What step is prioritized instead

Self-actualization or self-transcendence: purpose, integrity, contribution, coherence

Risk if sustained

Chronic financial stress, self-doubt, under-earning, or self-exploitation, especially if the individual lacks Farmer skills or a stabilizing context.

3. A gifted engineer speaks an unpopular truth, challenges groupthink, or follows an unconventional idea. Even when it leads to social isolation, misunderstanding, or rejection.

What steps are bypassed

Belongingness and love needs: approval, group inclusion, relational safety

Esteem needs: prestige and reputation

What step is prioritized instead

Cognitive integrity / truth / understanding (often overlapping with self-actualization)

Risk if sustained

Loneliness, marginalization, a stalled career path, loss of informal power, or internalized self-doubt (“maybe I really am the problem”).

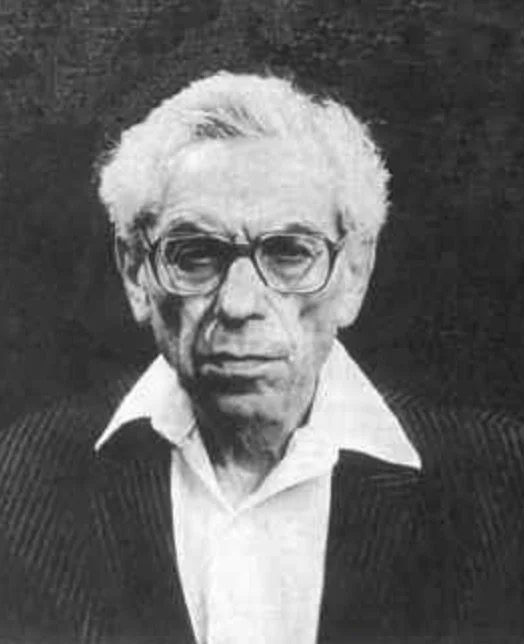

when pushed to the extreme: Paul Erdős

Paul Erdős (1913–1996) is almost a caricature of Maslow in reverse. He had little property, lived itinerant (traveling from colleague to colleague), and often let others take care of practical matters, so that he could do what he lived for: solve mathematical problems. Wikipedia sums it up sharply: "possessions meant little... most of his belongings would fit in a suitcase... he spent most of his life traveling... to the homes of colleagues."

Erdős was one of the most productive mathematicians in history. He lived almost without possessions, rarely had a permanent home, and traveled continuously from colleague to colleague. Others often took care of meals, housing, and daily logistics so he could focus entirely on mathematics.

To Erdős, solving mathematical problems was not a career. It was a calling. Security, ownership, and comfort were secondary at best.

The following quote, sometimes erroneously attributed to Erdős himself, shows the underlying mechanism perfectly: input → focus → output, with minimal interest in comfort.

“A mathematician is a machine for turning coffee into theorems.”

His life shows something important: when the drive for meaning and intellectual challenge is strong enough, people may reorganize their entire lives around it, even if that means sacrificing stability or conventional success. What mattered was the hunt: the elegance of a proof, the beauty of a theorem, the joy of intellectual discovery. His life was radically optimized for meaning rather than for stability.

Erdős is not a role model to be copied wholesale. He is, however, an extreme but clarifying case that reveals a deeper motivational structure shared, although usually in less visible form, by many gifted individuals.

“There are three signs of senility.

The first sign is that a man forgets his theorems.

The second sign is that he forgets to zip up.

The third sign is that he forgets to zip down.”

So why does the pyramid flip for the gifted?

1. Maslow himself left room for this

Maslow’s model is often presented as rigid, but he explicitly noted that human motivation is not (strictly) linear. Higher needs can dominate even when lower ones are only partially fulfilled. In later work, he introduced ideas such as self-transcendence, i.e. motivation driven by truth, beauty, or contribution beyond the self.

For some people, especially those with high cognitive intensity, these higher motives are not a luxury. They are the engine.

2. Intensity changes priorities

Many gifted people experience the world with unusual intensity. They think deeply, feel strongly, and become highly absorbed in problems that matter to them.

This can lead to:

Extreme focus (“forgetting to eat” is not a metaphor),

a Low tolerance for superficial goals

and Disinterest in status or routine rewards.

When meaning is absent, motivation collapses. When meaning is present, almost everything else becomes negotiable or optional. Even up to a point of thinking you can do completely without it. And yes, for some this includes people as well.

Rerversed Maslovian Piramid for the Gifted (in Dutch), © Your Evolving Self, 2026.

Self-Realization acts as the base and Physical Needs form the capstone.

3. Meaning before belonging

Where many people seek motivation through social belonging or external validation, gifted individuals often prioritize coherence and truth.

They would rather:

Work alone on something meaningful than belong to a group that feels empty,

Follow an internal compass than adapt to social expectations

and Solve a hard problem than feel safe but bored.

This helps explain why gifted people sometimes feel “out of sync” with environments that reward conformity, predictability, or hierarchy.

4. The gifted hunter mindset

From an evolutionary perspective, some people are wired as explorers rather than maintainers.

These Gifted Hunters are driven to:

Search for what does not yet exist,

Question assumptions,

and Venture into uncertainty.

For this type of person, safety is never the starting point. It is something to be managed after the hunt is underway based on what is encountered. The search itself provides energy, direction, and identity.

The hidden risk: neglecting the basics

There is an obvious downside to a reversed pyramid. When meaning always comes first:

The body is treated as an inconvenience,

Rest and recovery are postponed indefinitely,

and Financial, social and practical matters are ignored until they become crises.

Paul Erdős could live the way he did because others quietly provided structure around him. Most people do not have that luxury. Life eventually always catches up with you. The challenge for gifted individuals is therefore not to suppress their drive but to support it.

What to do when you’re ‘Afflicted’?

1. Stop judging yourself by the wrong yardstick

If Maslow’s pyramid feels upside down, that does not mean something is wrong. It means the standard model does not fully describe how you are motivated.

2. Treat basic needs as infrastructure, not inspiration

Food, sleep, money, and routines do not have to be meaningful. They just have to work so they stop competing with what truly matters to you.

3. Separate ‘searching for meaning’ from ‘self-sacrifice’

Living for something bigger does not require destroying yourself in the process. Personal sustainability is not a betrayal of purpose. Reciprocity is a must (think: relationships).

4. Build support structures consciously

If your mind naturally lives at the top of the pyramid, you may need external systems (habits, relationships, arrangements and structures) to stabilize the base. Not to limit your drive, but to anchor and protect it. Teaming up with an Intelligent Farmer might just do the trick.

A final reflection

Maslow’s pyramid describes a common human pattern not a universal one. Also, as human motivation is not linear when viewed from the original pyramid, the same applies to the Reversed Maslovian Pyramid. The pyramid shape is in this respect an abstraction but it does give you a clear framework you can work with.

For many gifted people, life begins with the question “Why?”, not “Is this safe?” The task is not to force yourself into the pyramid, but to build a stable foundation underneath your deepest motivations, so they can endure.

The key take-away is thus that where for more average people self-actualization is just a ‘nice to have’, for the gifted it is an absolute ‘must’. It is the engine that drives the whole show. And if that’s the case, don’t fight it but start designing your life around it, making sure all of your basic needs are met so you sustain your Long Hunt.

You might be gifted, but you’re also just another human being.

Dirk Anton van Mulligen

Your Evolving Self — exploring giftedness, development, and the art of guiding exceptional minds.

A big thank you to Crystal Cook-Marshall for pointing me in the direction of Paul Erdős and his Open Mind.

I am currently writing The Gifted Hunter, a foundational work on leadership and innovation under complexity, focused on the role of gifted, highly capable individuals who operate at the edge of existing systems and carry responsibility for renewal when stable structures begin to fail. The ideas in this article are part of the same body of work and are drawn directly from the strategic challenges I encounter in executive practice.

© Dirk Anton van Mulligen, Your Evolving Self, 2026.

Please note: This article is the result of regular and long reflection on this matter, supplemented with my experiences with gifted people. In other words, I put a lot of time and energy into it. No part of this article may therefore be reproduced without acknowledging the source and author. If you want to use more than a single quote or insight, please contact me for permission.